NEWS

2024-09-24

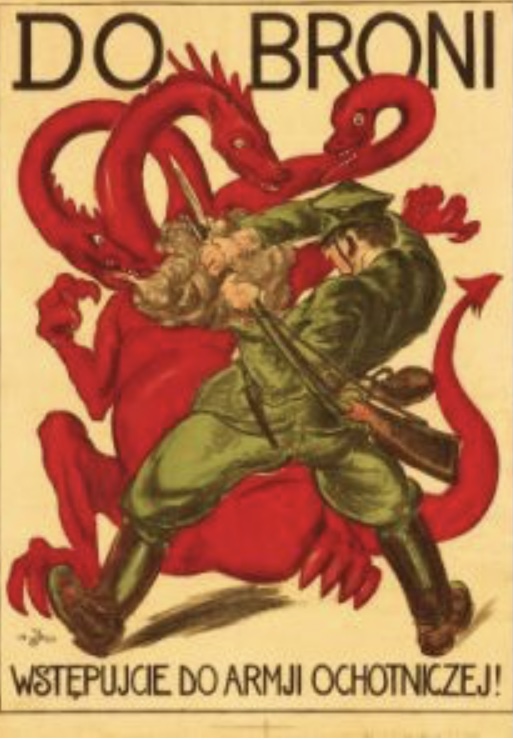

The Red Plague from the East / The Winds of War

A poster from the 1920 war, photo: public

domain

Authors: Maciej Paweł

Grzechnik, Hanna Sztuka

The

generation of breeders for whom the wartime fate of Polish Arabian horses was known and obvious

enough that the facts related to them did not need not only a comment, but even a reminder, is

leaving our world. At the same time, a new generation of breeders has grown up for whom obvious

facts are no longer obvious and there is a need to describe and remind of them

concisely.

“Red

plague

We're waiting for you, O red

plague

To save us from the Black

Death:

Waiting for a

salvation

To be welcomed with

disgust

By a country that's already hanged and

quartered

We await you, our immemorial

enemy

And blood-stained mass murderer of our

brothers...”

- Józef

Szczepański

Introduction

When in 1772 Russia, Prussia and

Austria carried out the first partition of Poland, the process of destroying the Polish-Lithuanian

Commonwealth began, a country which had existed for almost 400 years, an extraordinary state with a

system much ahead of its time. Its origins date back to 1385, when the Kingdom of Poland and the

Grand Duchy of Lithuania concluded a personal union. Based on an agreement between the states, the

Union of Lublin concluded in 1569 allowed for the creation of a Polish-Lithuanian federation

composed of equal members. As a result, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was established, whose

"golden age" was also a period of dynamic development of horse breeding throughout the country.

Equus Polonus was the most valued horse in Europe between the 16th and 18th centuries. So much so,

that during the years of great wars with Turkey and the Tatars, King Władysław IV introduced a ban

on the export of Polish horses, which were eagerly purchased by neighboring countries. The next

three partitions in the 18th century, followed by the Napoleonic Wars at the beginning of the 19th

century, caused the first wave of decline in horse breeding in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

For this reason, the first state stud farm was established to meet the needs of the eastern

(Russian) invader, located in the village of Wygoda near Janów Podlaski. However, most of the

magnate stud farms in the Russian partition ceased to exist or were only able to recover from the

collapse to a very limited extent. The economic situation in the Russian partition did not allow

Poles to develop expensive breeding, and after the fall of the November Uprising against Russia in

1831, and then the January Uprising in 1864, attempts were made to limit horse breeding on Polish

lands and even prohibit the Polish nobility from owning horses. The restrictions were dictated by

strategic considerations, i.e. cutting off Poles from the possibility of using horses in the fight

against the invader - Russia. Only a few stud farms - now legendary for this reason - such as:

Sławuta, Biała Cerkiew, Sachny, Jarczowce, Antoniny and Gumniska, continued and cultivated horse

breeding in the old style. As a result, in the second half of the 19th century they reached a high

breeding level, especially visible in the breeding of pure-bred Arabian

horses.

Wojciech Kossak, Uhlan fighting with a

Cossack, Warsaw 1930, source: Galeria Klasyki

The first wave of the plague

It came in 1917 with the Bolshevik rebellion, which caused the destruction of horse

breeding, which had been developing continuously for several centuries in the eastern borderlands of

Poland. The herds of Sanguszko, Potocki, Branicki, Dzieduszycki and many others were exterminated.

Tsarist horses from the stud farm in Janów Podlaski were evacuated deep into Russia and, without any

loss to Polish breeding, never returned. In eastern and southern Poland, where there were many

breeding farms for pure-bred Arabian horses before World War I, few horses survived. Fate brought a

tragic end to these farms. This is how Dr. Skorkowski described the destruction of Sławuta in

November 1917 in his "Stud Book": "The famous stud farm in Chrestówka, plundered by the Bolshevik

hordes in 1917, ceased to exist. It ceased to exist together with the wonderful Polish residence in

the borderlands of Sławuta, in the ruins of which died the faithful to his land to the very end, an

over eighty-year-old man, unspared by the barbaric Bolsheviks – Prince Roman

Sanguszko...”

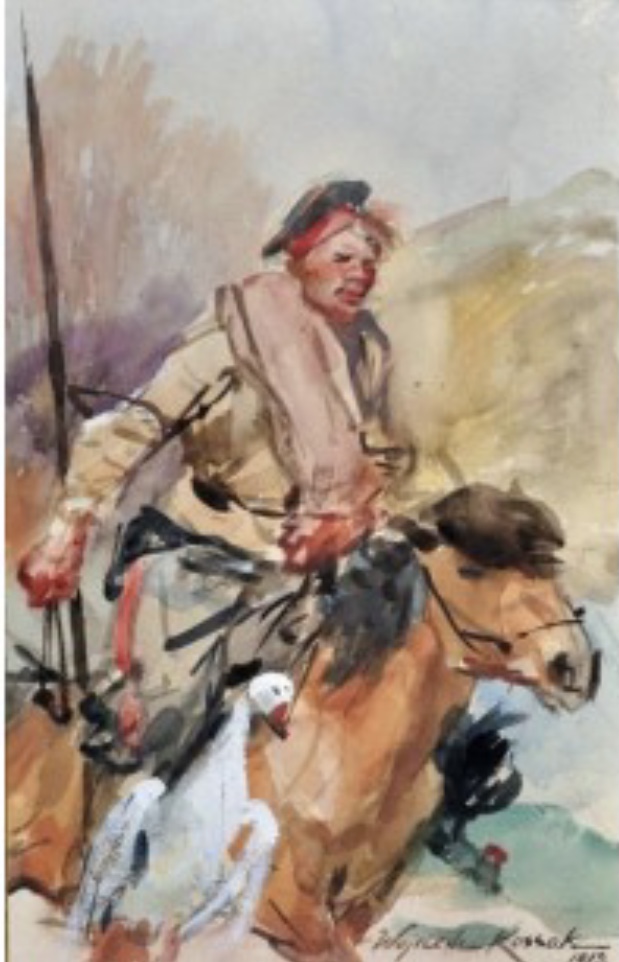

Wojciech Kossak, Pogrom, photo public

domain

Biała Cerkiew and Antoniny are also destroyed: "Sixty-plus

mares from the Biała Cerkiew stud farms go under the Bolshevik machine gun as 'horse

aristocracy'".

The Holocaust of Antoniny, which was seen with her own eyes in 1918

by the Polish writer Zofia Kossak-Szczucka (1889–1968), granddaughter of the painter Juliusz Kossak,

is described in a book published in 1922 entitled "Conflagration". Only twenty Arabians born in

Antoniny survived extermination, thanks to the servants devoted to their employers who hid them in

the forests "... from the mob enraged by Bolshevik principles." The surviving horses were brought to

the Potocki estate in Beheń in Volhynia, where breeding was continued.

The

stud farms in Małopolska: Jabłonów, Taurów and Zarzecze, plundered by Russian troops, were also

completely destroyed. In Pełkinie the youngsters survived, who by chance were not taken away by the

Russian troops as they had the strangles. The stud farm in Jezupol (of count Władysław Dzieduszycki)

is being liquidated, where after the Russian and Ukrainian invasion, only four mares survived and

were transferred to the State Stud Farm in Janów Podlaski. In the Małopolska region, the stud farm

in Gumniska (of Prince Roman Sanguszko) is being revived as one of the few, despite significant

losses.

Wojciech Kossak, Uhlan leading Russian

prisoners, photo: public domain

Many other stud farms also fell

victim to the red plague: in Borówek, Bronice, Dzieżbice, Jezierzany, Lipniczki, Miszewo-Murowane,

Niezdów, Patków, Podhajczyky, Regów, Szumsko, according to Skorkowski: "...all of them suffered to a

greater or lesser extent from the Russian troops or the much more ruthless German ones, who

systematically exported all our breeding mare material to Germany.”

Horses died, stud

farms were ruined, and documents were destroyed. The Biała Cerkiew stud book, kept continuously for

115 years (since 1803), which recorded the number, origin of individual horses and the records of

imported stallions, was lost. “Thus, the achievements of several generations of breeders from

1778–1918 were lost and everything had to be started anew.” – summed up the chapter devoted to this

period prof. Witold Pruski. As a result of these actions, only 10% of the pre-war condition of

Polish Arabian horse breeding survived: out of over 500 broodmares in our Arabian studs, only 56 in

1926 were entered into Section I of the Polish Arabian Stud Book. According to Skorkowski: "These 56

mares are the foundation of Polish Arabian breeding, from which she will be reborn - because she

cannot die, since she gave birth to Melpomene and Skowronek."

The loss of lands in the

east and the shifting of borders after World War I resulted in the fact that many stud farms,

especially those in the borderlands, were never reborn. New private stud farms were established,

which, although they did not have high-quality breeding material or economic potential even close to

the former borderland stud farms, achieved a very high level in the 20 years until the outbreak of

World War II. Today it is difficult to imagine world breeding without Amurath Sahib 1932, sire of

Arax, bred by Teresa Raciborska in Breniów, or Bałałajka 1941 of Mr. and Mrs. Bąkowski from

Kraśnica, dam of Bask and Bandola. Prince Roman Sanguszko from Gumniska, the heir to the Sławuta

farm, invested great resources to restore the glory of his breeding, of which only eight mares and

three stallions survived the First World War. The import of original stallions from Arabia in 1930,

ending a long tradition of using desert stallions, opened a new era not only in Poland, but also in

world breeding through the descendants of the then imported stallions. Kuhailan Haifi, d.b. 1923,

found among the Bedouins Ruala, produced in Janów Ofir (1933), who in turn was the sire of the

so-called the "big four", i.e. Wielki Szlem, Witraż, Witeź II and Wyrwidąb. The second import,

Kuhailan Afas, became famous as the ancestor of Comet (1953).

Wojciech Kossak, Cossack on a horse, 1913,

photo public domain

The former power was recreated from the remains

that were saved from the historical catastrophe of World War I. In the interwar period, breeding

slowly and systematically recovered from decline, and the leading role was played by Janów Podlaski

State Stud, where it implemented its own breeding program for pure-bred Arabian horses, carried out

with great success until 1939.

The second wave of the plague

The steppe and German

imperialism together with national and international socialism, in the autumn of 1939 shook hands

over Poland, which was once again thrown to the ground. Totalitarianism also reached Janów Podlaski,

a town lost on the Bug River in Podlasie, and the continuity of breeding was interrupted by not only

a wave of red plague, but also brown, devastating Polish farms.

After the outbreak

of war on September 1, 1939, a decision was made to evacuate the Janów herd and stud farm to the

east. The horses and staff set off on September 11 eastward towards Volhynia. As a result of the war

confusion, a wonderful crop of colts, sons of Ofir: Wielki Szlem, Witraż, Witeź II, Wyrwidąb and the

son of Lowelas, the stallion Wojski, were lost on the way. Due to injuries and tiredness of the

foals, some of the horses were also left behind in manors or at peasant farms. However, this

circumstance ultimately turned out to be very fortunate, because the horses left there survived and

after some time, together with Ofir's sons, returned to Janów. On September 17, upon hearing the

news that the Soviets had crossed the eastern border of the country, further evacuation no longer

made sense and the herd returned to Janów.

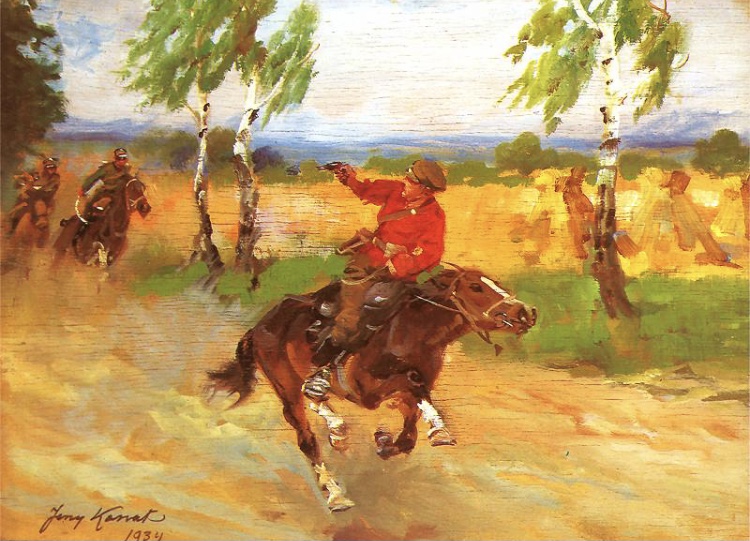

Jerzy Kossak, Pursuit of the Fleeing

Commissioner, 1934, oil on plywood, private collection

The Russians

who entered Poland reached Janów, where they robbed all the horses they found, as well as the

movable property of Janów Podlaski State Stud Farm. Thus, the best Arabian stud farm in Europe

ceased to exist. From the herd, which, according to data from 1938, amounted to 27 pure-bred Arabian

mares, only Najada (Fetysz - Gazella II) remained in Janów, as she could not be moved out of the

stall. Of these 27 broodmares, 6 went missing, and 20 of them and all the youngsters, including

young mares who returned from the racetrack in 1938, were taken to the Russian stud farm in Tersk in

the Caucasus. The mares from Janów had problems with acclimatizing there and in 1940, 3 of them

died, in 1941 another 3, and in 1942 as many as 5. Only 9 of them survived longer than 3

years.

Beginning with the outbreak of World War II in 1939 and ending in 1945, 143

pure-bred Arabian broodmares were stolen (or disappeared) from Poland. In 1946, the PASB registered

only 52 surviving mares recovered from Allied-occupied Germany, as well as mares rescued in the

country and Czechoslovakia, and a few that survived in Poland.

Jerzy Kossak, Pursuit of the Bolsheviks, oil

on board, private collection

The losses suffered by Poland as a

result of the invasion of Germany and Russia in 1939, and the subsequent crossing of the front with

Soviet troops marching towards Berlin, is a human history full of drama, but also of the systematic

plunder of Polish property and goods by both armies. Both took everything of value: gold, works of

art and culture, industrial and agricultural machinery. Farm animals were also eagerly robbed,

especially horses. The most valuable for the Germans and Russians were purebred horses, i.e.

Thoroughbreds and Arabian horses, although the occupier also did not despise half-bred sports

horses, mainly stallions. From today's perspective, it is difficult to understand that Polish horse

breeding, especially pure breeds, were competitive with German horse breeding before 1939, and

certainly at a higher level than the Russian breeding at that time, which is why horses from Poland

were a valuable asset to the invaders. The Germans had a lot of time, because they occupied Poland

from the fall of 1939 to the beginning of 1945, so the plundering was systematic and

institutionalized. The Russians, on Polish soil in the years 1939-1941, plundered everything they

could get their hands on, and at the turn of 1944/45, when they were going through Poland to Berlin,

there were not many valuable horses left, so most often there was simple front-line robbery. At the

end of 1944, the Germans decided to take away from Poland all stallion herds and stud farms existing

under their control, including the Wehrmacht stud farms that they had organized during the war,

which collected breeding horses scattered as a result of the war or, more often, taken away from

private owners. Each of the invaders took the stolen horses in their own direction. The Germans took

the most valuable Polish horses deep into the Reich, where eventually, after the end of the war, the

largest group of them found themselves in the British occupation zone. In this zone, on the

initiative of Polish officers released from the Oflags, the Polish Stud Board in Germany was

established, thanks to which Poland regained over 1,600 breeding horses in the years 1945-1947,

including a significant group of pure-bred Arabian horses. Some of the horses that found themselves

in the American occupation zone were treated as war spoils of the US Army and were sent to the USA

despite objections from the Polish Stud Board in Germany. The fate of the horses that found

themselves in the Soviet occupation zone in Germany and in western Poland, if not killed (eaten?) by

Soviet soldiers, were robbed and taken to the east or remain unknown.

The third wave - the plague of communism

Jerzy Kossak, Uhlans in pursuit of the

Bolsheviks, 1935, oil on board, private collection

World War II

definitely determined the end of an era and the division of Europe. The wartime fate of Polish

Arabians is the subject of many articles and books. After the war, state stud farms and people

associated with them undoubtedly played a great role in rebuilding purebred horse breeding in

Poland. Their contributions cannot be overestimated. Nevertheless, it was the state that contributed

to subsequent misfortunes that befell the country and, of course, the breeders and breeding under

the rule of the new system. Pursuant to a special decree, farms with an area of more than 50 ha (in

3 voivodeships - more than 100 ha) were nationalized. It was a time of bloody repression,

persecution of people with different views, taking away property, nationalizing land, factories and

houses. Communist courts convicted people who fought not only the Soviet, but even the German

occupier. The Security Office ruthlessly dealt with political opponents of the regime. The "Iron

Curtain" cut off Poland from the democratic world for many years. The new authorities viewed the

breeding of purebred horses with reluctance. In the 1950s and early 1960s, the Arabian horse was

considered a bourgeois relic, a whim of the former ruling class, a luxury good that no one in the

new, proletarian system needs. Only draft horses were appreciated as necessary in a backward country

for agriculture and transport. Regardless of their origin, the breeding animals that survived the

war became the property of the state.

Anna Bąkowska, the owner of the stud farm in

Kraśnica, regained her two extremely valuable mares, including Bałałajka, but for a short time,

because both were eventually taken to the state stud of Albigowa. "It was a happy coincidence that

we acquired the grey mare Bałałajka" - wrote Prof. Witold Pruski about this event in the chapter

devoted to this stud farm.

“Acquisition” was a euphemism and simply meant

confiscation. Anna Bąkowska was the only private breeder to obtain compensation from the state, but

it was equal to the cost of a working horse at that time. Anna Bąkowska and her daughter Ewa finally

paid for their fight against the communist state in 1948 when they were arrested on charges of

helping the Home Army*.

Repression, i.e. denying the plague

After World War II,

attempts were made to erase the memory of previous times. It was forbidden to speak about the

destruction caused in 1917–1918, as well as the robbery in September 1939. A characteristic

testimony of this approach is the previously cited work of Prof. Witold Pruski (published in 1983).

The chapter "Devastation caused by the First World War" takes up less than a page! The censorship

allowed only the following sentence: "After Poland regained state sovereignty in 1918, only a small

number of horses from Sławuta and Antoniny were found on its territory, but nothing remained from

the Biała Cerkiew and other borderland stud farms." There is not even a mention of the destruction

and murders committed by the Bolshevik invaders - the red plague from the

east.

Wojciech Kossak, Trumpeter with a horse,

photo public domain

The old specialists were removed, and only

people who got along with the new authorities were sent to the farm. The legendary Polish breeder,

Bogdan Ziętarski**, who bred in Gumniska and then saved from Soviet plunder the only representative

of the Ukrainka damline from Sławuta, the mare Forta 1943, and the only job with horses he could get

from the communists was in the foaling farm for draught horses in the Milicz State Agricultural Farm

where he died in obscurity in 1958. Some of the officers involved in the recovery of Polish horses

as part of the activities of the Polish Stud Farms Board in Germany remained abroad, some returned

to Poland and found employment in state breeding, but some were harassed and sent to prison during

the Stalinist era.

It is impossible to count how many valuable Arabians were lost in

state stud farms due to communist regulations, which were theoretically supposed to ensure their

survival. Stud farms were assigned a number of exact broodmares, limiting their development, and

many horses were not given any chance and were simply sent to slaughterhouses. According to Anna

Dębska, a sculptor and breeder who fought for years to save at least some valuable horses, the First

Secretary of the Polish United Workers' Party, Władysław Gomułka (1956-1970), who considered Arabian

horses as "freeloaders", had a hand in this. However, thanks to significant foreign exchange

revenues, breeding was maintained, and from the beginning of the 1960s, its dynamic development took

place in Poland, and as it was highly profitable, it was reserved exclusively for state stud farms.

Private breeding of Arabian horses after World War II began to develop dynamically only after 1989

and today it is already at a world level.

The revival of Arabian horse

breeding in Poland, both public and private, was possible thanks to the deep tradition of breeding

oriental horses, deeply rooted in Polish culture. Polish Arabian horse breeding, repeatedly

destroyed by the red or brown plague, has always been conscientiously rebuilt by subsequent

generations. In the Arabian horse breeders' community, much attention was paid to documenting the

breeding and its history. Arabians are a breed of horses whose breeding has been maintained at the

highest world level by successive generations of Poles for over 300 years. Since the beginning of

the 21st century, we have lived in the blissful belief that the disasters of the 20th century, which

first destroyed the borderland stud farms and then completely robbed us during World War II, will

never repeat themselves.

Another wave of the plague

On February 24, 2022, the

sense of security in our part of Europe was shattered, although it took a few weeks for the rest of

the world to come to terms with it. The red plague started, as always, from the east. It even

approached the vicinity of Kiev, murdering people and destroying cities. As reported by the

independent Belarusian news channel Nexta, on March 22, 2022, the Russian army set fire to a stud

farm in the town of Hostomel on the outskirts of Kiev, and most of the animals were burned alive -

we read in the message. Whether and when can a plague from the east reach Poland, we still cannot

predict after more than two years of war in the Ukraine. But it turns out that the plague of

communism in people's heads is a disease that almost never goes away - it cannot be cured. Years

ago, when our state created post-war breeding, it did so on the ruins of private breeding, feeding

on its expense and creating its own class of breeders: the stud aristocracy. Today, when private

breeding is taking a breather, the posthumous stud aristocracy are like a red plague that penetrates

and spoils healthy organs, preventing them from functioning properly.

The elite, although

now dying out, stud aristocracy in Poland has been defending its privileges for years, using

contacts acquired through inheritance with representatives of European institutions and with

politicians of each subsequent government camp. So its spins a story in the media about the only

righteous people and mythologizes the history of state breeding. Unexpectedly, as we prepare for

another invasion from the east or west, we may witness how Polish breeding will ultimately be

destroyed by the Poles themselves. The state-owned breeding, because private breeding is in the

hands of breeders who are increasingly disgusted when it comes to watching the senseless actions in

state-owned studs.

*Home Army, clandestine armed forces of the Polish

Underground State. The largest underground army in occupied Europe fighting against the German and

Soviet occupiers.

**Bogdan Ziętarski, breeder of the Sanguszko stud farm in

Gumniska. As the leader of an expedition to Arabia in 1930, he brought to the country the

epoch-making stallions Kuhailan Haifi d.b. for breeding, Kuhailan Afas d.b. and Kuhailan Zaid d.b.

Bogdan Ziętarski, commissioned by the Arabian Horse Breeding Society, developed racing programs for

Arabian horses in 1928, which have been operating with minor changes for the last 98 years, and the

Polish performance test for Arabian horses has always been the basis for the success of Polish

breeding and the spread of the Pure Polish horse type.

Bibliography:

- Luft Monika: „235 lat polskiej hodowli prywatnej koni czystej krwi. Czy pamięć udało się wymazać?” polskiearaby.com 24 listopada 2013

- Pankiewicz Roman: „Polska Hodowla koni czystej krwi arabskiej 1918-1939.” Petroniusz Frejlich 2002.

- Szczepański Józef ps. Ziutek, „Czerwona zaraza”, Sieci 40/21. Żołnierz, poeta, zginął na barykadach Warszawy (1944) w wieku 21 lat.

- Sztuka Hanna: „Józef Tyszkowski i Jego Epopeja. Wojenne losy polskich koni arabskich. 1939-1946, cz. 1.” polskiearaby.com

- Sztuka Hanna: „Niemcy w Janowie. Wojenne losy polskich koni arabskich 1939-1946, cz. 2.” polskiearaby.com